In the short term, there seems to be a consensus among economists that the amount of money in circulation has some impact on the economy’s movements. Additionally, there is agreement that, to some extent, fine-tuning is possible by regulating the money supply. The usual target of this fine-tuning is the level of prices. Since 2000, Korea has been implementing monetary policy with the goal of achieving an inflation rate of around 2.5%.

Every country has some form of central bank. Unlike other countries’ central banks, the United States maintains a ‘decentralized central banking system.’ There are twelve regional Federal Reserve Banks, which are overseen by the FRB in Washington. The FRB chairman is called the ‘economic president’ due to their significant influence, but the actual FRB system is quite decentralized.

When we refer to the FRB, we are not talking about the twelve regional Federal Reserve Banks but the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, which oversees these banks. The ‘B’ in FRB stands for ‘Board,’ not ‘Bank.’ As mentioned, it is true that private banks in the United States are shareholders of the Federal Reserve Banks, but it’s not as easy as some conspiracy theories suggest for financial magnates to influence the FRB’s monetary policy decisions for their own benefit.

The ownership structure of the Federal Reserve Banks in the United States is due to the Federal Reserve Act, which mandates that any bank operating commercially within the U.S. must own stock. This means that becoming a shareholder in a Federal Reserve Bank is different from being a shareholder in a regular corporation or a member of a profit organization. The shareholders of the Federal Reserve Banks have obligations but no rights. The FRB’s decision-making process involves a committee of FRB directors, but the chairman and directors are not appointed by the shareholder banks but by the government. The debate over whether the Federal Reserve Banks should be owned by the government or by private entities fundamentally concerns how to ensure the independence of the central bank from the government rather than deriving profit from ownership.

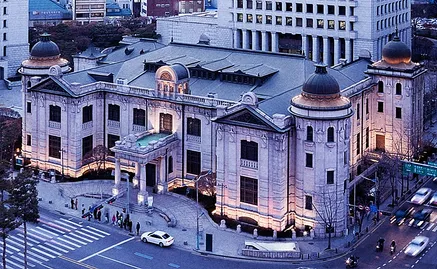

It’s possible that due to initially following the American financial system, South Korea has established a Monetary Policy Committee within the Bank of Korea. Back in 1997, the position of the chairman of the Monetary Policy Committee was held by the Minister of Finance, but now it is held by the Governor of the Bank of Korea. This illustrates that Korea, like the United States and Europe, agrees on the importance of keeping the central bank independent from the government.

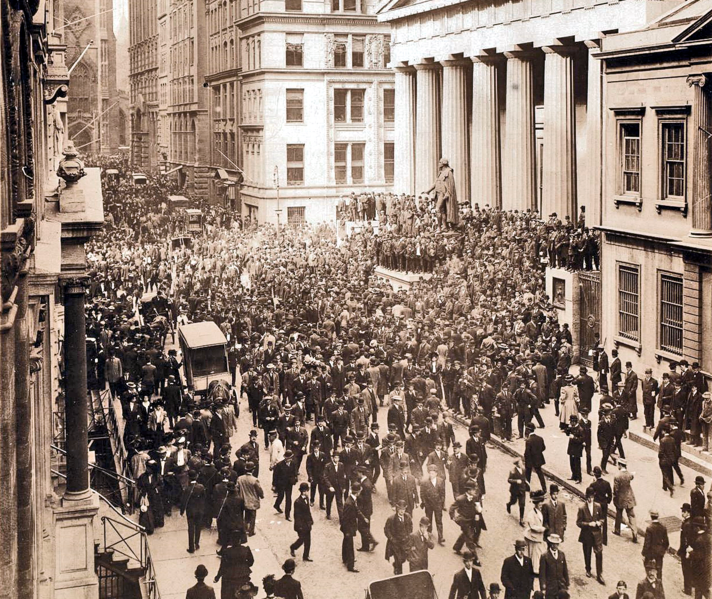

In the 18th and 19th centuries, the United States had a central bank overseeing monetary policy twice, both of which eventually disappeared. This was because the prevailing attitude at the time was to leave everything to the “invisible hand” of the market. However, the need for a central bank reemerged following a bank run that started in New York in 1907, leading to the establishment of today’s system through the Federal Reserve Act of 1913. So, how can a central bank like the U.S. Federal Reserve control a country’s currency? Let’s briefly review the tools of monetary policy.

Lending

The easiest way to increase the money supply is to increase lending. Just as banks lend funds to businesses or households, the central bank lends money to banks. However, businesses or individuals cannot directly ask the Bank of Korea for loans. If they truly want to borrow from the Bank of Korea, they must explore various policy financing options and approach the banks accordingly.

Conversely, if the government wants to lend money to a particular enterprise, it also must do so through banks. This process used to involve commercial banks discounting the bills of enterprises, and then the central bank would rediscount these bills to provide funds, hence the term “rediscounting system.”

Banks primarily obtain funds from the financial markets where they trade with each other when they face a shortage of funds. However, for the government to support small and medium-sized enterprises or special companies, this method serves as a useful policy tool. This rediscount policy is what comes to mind when we hear “policy financing.”

In South Korea, when banks lend to specific sectors, the Bank of Korea has supported these banks with lower interest rates for a portion of these loans. However, considering that this method could increase the money supply and contravene market principles, South Korea introduced a total loan quota system in 1994. This system aims to prevent indiscriminate and generous lending by setting a target money supply in advance. Indeed, one of the biggest problems in our financial market has been policy-driven financing, where the government and conglomerates have collaborated to direct bank funds to their desired destinations, with consequences to bear.

In any case, by setting an overall limit in advance and distributing funds to each bank under certain conditions within this range, the central bank ultimately controls the national money supply by lending to private banks. This is why the central bank is also called the ‘lender of last resort.’

Open Market Operations

Another straightforward method for the central bank to control the money supply without providing loans involves government bonds initially printed by the government and handed over to the central bank. The central bank can use these bonds to adjust the national money supply. For instance, selling the bonds reduces the money circulating in society as the cash moves into the central bank. In essence, it exchanges liquid money for less liquid assets. To increase the money supply, conversely, the central bank buys these bonds.

This simple policy is the most fundamental and widely used tool by most central banks and is known as open market operations. While various government bonds can be used for open market operations, central banks may issue specific bonds, known as monetary stabilization bonds or MSBs, to control the money supply. These were introduced by the Bank of Korea to retrieve the circulated money supply due to a shortage of government bonds available for open market operations in the past.

Furthermore, when buying or selling government bonds, a mechanism known as Repurchase Agreements (RP) is often used instead of direct transactions. Thus, RP transactions involve exchanging funds using government bonds as collateral. When the Bank of Korea needs to absorb liquidity from the market, it borrows funds from private banks using government bonds as collateral in what’s known as RP selling. Conversely, RP buying refers to the Bank of Korea lending money against government bonds held by financial institutions. Essentially, though the transactions are verbally based on buying and selling bonds, they effectively operate as such.

Interest Rate Control

When adjusting the money supply through the buying and selling of government bonds, interest rates serve as a complementary policy tool. The benchmark interest rate, set by the central bank, applies to these transactions. Although rates are generally determined by supply and demand, the central bank influences banks’ borrowing costs, thereby affecting loan prices. The cost of funds for banks is determined by the interest rate paid to borrow from the central bank, known as the benchmark interest rate.

At one point, the call rate, which applies to short-term transactions between financial institutions, was used as the benchmark rate. However, the call rate began to “fix” due to expectations that the Bank of Korea would adjust it to match the benchmark rate regardless of circumstances.

Therefore, in March 2008, the benchmark was shifted from the overnight call rate to the 7-day repurchase agreement (RP) rate, making the call rate more responsive to supply and demand.

Interest rates represent the cost of money. Like any price, they should be determined by market supply and demand to function properly. However, when used as a policy tool by the government, as with the call rate example, rates lose some of their market functionality, becoming primarily policy-driven.

Interest rates have a significant policy impact due to their broad ripple effects. When the central bank increases the money supply or lowers the benchmark rate, short-term rates drop first. This encourages financial institutions to borrow short-term funds at lower costs for investing in long-term securities like corporate or government bonds, increasing demand and bond prices, which in turn lowers interest rates further.

Lower bond yields prompt banks to increase lending to individuals and businesses for higher returns, necessitating lower lending rates. Lower lending and corporate bond rates mean cheaper capital for businesses, encouraging investment and potentially driving economic growth.

Interest rates also affect individuals. Lower rates discourage savings and increase currency circulation, whereas higher rates encourage savings over spending. High rates deter borrowing, making saving more attractive and thus reducing spending.

Generally, lower interest rates lead to higher stock prices as lower returns from deposits and bonds push investors towards stocks as an alternative investment. Stocks and bonds offer alternative investment options, and a rise in stock prices increases wealth, encouraging investment and consumption, thus stimulating economic activity.

Change in the Reserve Requirement Ratio

Another way the government can control the money supply is through the reserve requirement ratio mentioned in the process of banks creating new money. Banks must keep a certain percentage of their deposits at the central bank, rather than lending out all of their deposits. This policy was introduced to protect depositors from bank failures, ensuring that banks have some money reserved in case many people withdraw their money at once.

However, once it was realized that the reserve requirement ratio could be used to control the amount of money, it became a tool of monetary policy. Raising the reserve ratio means banks must deposit more money at the central bank, reducing the money supply in the economy. Conversely, lowering the reserve ratio allows banks to deposit less money, increasing the money supply in the economy.

Since reserve requirements do not earn interest, they can worsen the financial institutions’ balance sheets and raise issues of fairness among financial institutions that do not have reserve requirements. The reserve requirement ratio varies with the type of deposit and changes over time, but the average in Korea is about 7%.

Another factor limiting banks’ lending is the BIS ratio, which stands for the Bank for International Settlements’ Capital Adequacy Ratio, set in July 1988 as an international standard to ensure banks’ capital adequacy. It recommends banks to maintain a certain level of equity capital against risky assets, meaning banks need to retain a percentage of their own capital in case they cannot recover most of the loans made to failed businesses. The reserve requirement also advises banks on how much cash to hold, effectively limiting banks’ liquidity in two ways.

The BIS standards can also be an obstacle to government monetary policy. For example, if the economy worsens and the money supply needs to be increased, banks may hesitate to lend because they are focused on meeting the BIS standards, making it difficult for the central bank to achieve its goals.

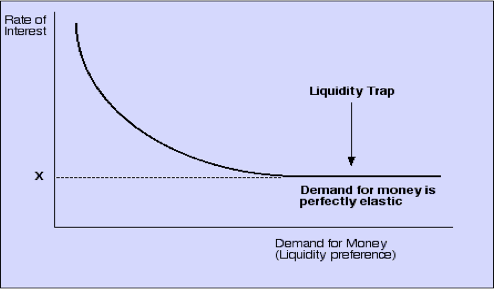

If monetary supply and interest rate controls stabilize the currency and positively affect the economy, the government and economists’ roles would be easier. However, the problem is that it doesn’t always work as intended. During economic downturns, even if the authorities increase the money supply, it might not stimulate economic activation if the increased currency does not circulate in the market. This situation is known as the liquidity trap.

Liquidity Trap

Central banks release funds hoping that banks will pass them on to businesses, which in turn will generate profits, pay interest to the banks, reward their employees and shareholders, and stimulate consumption, thereby rejuvenating the national economy. This virtuous cycle is what policymakers hope for when they lower interest rates and inject money into the economy. However, during economic downturns, a persistent issue known as the “liquidity trap” arises.

A liquidity trap occurs when, despite the central bank’s efforts to increase the money supply and lower interest rates, the flow of money does not trickle down to the real economy. Consequently, contrary to the government’s intentions, the money supply in circulation does not increase, nor do loan interest rates decrease.

In the event of a prolonged economic downturn and a perceived reduction in the money supply, authorities worldwide may attempt to stimulate the economy by increasing the money supply. This was evident during the 2008 global financial crisis when countries responded by increasing their money supplies and lowering benchmark interest rates to boost liquidity and avert a credit crunch. Despite these efforts, the expected increase in funds within the market did not materialize for several reasons.

First, financial institutions, seeking to improve their financial health, may be reluctant to release funds. Second, companies that previously received loans easily now face increased risks, making it difficult for them to secure funds. Third, both individuals and businesses may prefer holding onto cash, perceiving it as safer, leading to no increase in the money supply. Fourth, the money supply can only grow if borrowing increases, but economic uncertainties prompt companies and individuals to pay off existing debts rather than incur new ones. Consequently, the money supply decreases because debt creates money. If everyone rushes to repay debt, the available funds in the market rapidly decline, complicating the situation whether money is injected or withdrawn. This predicament is known as the “liquidity trap.”

This scenario played out in early 2009 in South Korea. While the central bank increased the money supply, the Financial Supervisory Service urged commercial banks to raise more capital to improve their reserves. Given the existing Basel II requirements, banks had to attract more money to boost their capital reserves, further constraining the already tight money flow.

Lending to businesses became unthinkable. The risk associated with previously sound companies increased during economic downturns, and individuals became more cautious, anticipating potential issues. With no one borrowing, the creation of money through debt decreased, thwarting the government’s hopes of increasing the money supply. The liquidity trap is not a modern-day phenomenon; it was also evident during the Great Depression in the United States and Japan’s real estate bubble. Falling into this trap inevitably creates a dilemma for monetary policy.

Ideally, if the government could efficiently regulate the economy through adjustments to the money supply or interest rates, it would be beneficial. However, the effect of money is delayed and diffused through various processes. Furthermore, with the opening of national financial markets and the emergence of diverse financial products, managing the economy through monetary supply has become increasingly challenging.

Moreover, economic growth or wealth increase fueled by monetary expansion is not free. If mishandled, it could lead to inflation and the formation of financial asset bubbles. Should economic warning signs emerge, we could potentially face various financial crises and ultimately a comprehensive economic crisis.