There are basically two types of exchange rates that represent the value of a country’s currency: fixed exchange rates and floating exchange rates. A fixed exchange rate is a value determined by the government at a certain level, while a floating exchange rate is determined freely in the market. Both types have their advantages and disadvantages, and ultimately, choosing one means paying a price for not choosing the other.

The fixed exchange rate system, which stabilizes the exchange rate, can be a good means to facilitate trade transactions and protect the country’s economy from foreign speculative capital, due to the stability of the currency value. However, this is not free. In return, significant changes must be made in the face of international balance of payments imbalances, which can lead to turmoil. Moreover, the determined exchange rate is naturally not the market price, which leads to the prevalence of black markets. On the other hand, the floating exchange rate system has the advantage of being able to resolve temporary market imbalances on its own in the medium to long term because it reflects market prices. The price to pay for this, of course, is the uncertainty of currency value.

Robert Mundell, who won the Nobel Prize in Economics in 1999 for his contributions to the European Monetary Union by tying 12 countries’ currencies to a fixed exchange rate system called the euro, emphasizes that the high economic growth rates recorded by China, Hong Kong, Japan, and even Germany in the past were all thanks to the fixed exchange rate system. However, most countries have already adopted the floating exchange rate system. Countries that insist on a fixed exchange rate system include Hong Kong, which implements a fixed exchange rate system linked to the US dollar through a peg system. Our country started implementing a limited floating exchange rate system in 1980, changing from a fixed exchange rate system, and introduced a fully floating exchange rate system after the IMF in 1997.

The Determination of Exchange Rates

An exchange rate is the exchange ratio applied when swapping currencies of two different countries. For example, if the exchange rate between the South Korean won and the US dollar is 900 won/1 dollar, it means that 1 dollar can be exchanged for 900 won, and vice versa.

At the same time, the exchange rate also represents the value of a country’s currency. If a country is considered a corporation, the value of its currency is akin to its stock price. If exchange rates are freely determined in the market by supply and demand, then that is the case.

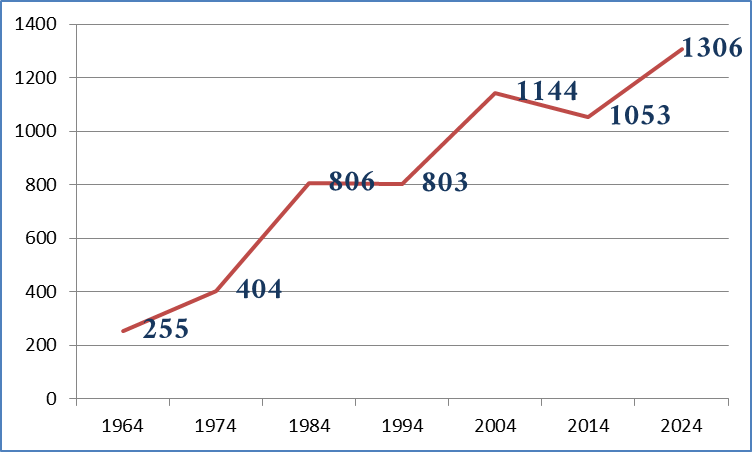

There was a time in the 1970s when the exchange rate was in the 500 won range. As of 2024, it fluctuates between 1200 and 1300 won. However, the exchange rate in the 1970s was a fixed exchange rate announced by the government, not a price determined by the market. This is evidenced by the fact that more Korean money could be exchanged in the black market, the underground dollar market, than at the official exchange rate. Starting with a fixed exchange rate of 125 won per dollar in 1962, South Korea gradually adopted a market-determined exchange rate system, changing to 480 won in 1974 and 580 won in 1980. Following the IMF financial crisis, from December 1997, the exchange rate system changed to a true floating exchange rate system, where the exchange rate fluctuation is unlimited and determined by the market, and it has continued to this day.

History of Exchange Rate Systems in Korea

- 1945. 10 ~ 1964. 5: Fixed exchange rate system

- 1964. 5 ~ 1980. 2: Single floating exchange rate system: A system that changes the value of each country’s currency according to the supply and demand conditions in the foreign exchange market. However, in reality, it was a fixed exchange rate system determined by the Bank of Korea.

- 1980. 2 ~ 1990. 3: Multiple currency basket system: A method of calculating the USD/KRW exchange rate by considering the exchange rates of several countries with which Korea has a large trade volume.

- 1990. 3 ~ 1997. 12: Market average exchange rate system: An exchange rate system adopted during the 1997 foreign exchange crisis, where the exchange rate is determined by supply and demand in the foreign exchange market, but the daily fluctuation range of the USD/KRW exchange rate is limited within a certain range.

- 1997. 12 ~: Free floating exchange rate system

However, the exchange rate of the South Korean won against other currencies like the Japanese yen is not determined in the foreign exchange market due to the small volume of transactions. Instead, it is calculated indirectly using the exchange rates between the US dollar and other currencies. For instance, if 1 US dollar equals 900 won in the Seoul foreign exchange market and the exchange rate between the US dollar and the Japanese yen is 1 dollar to 100 yen in the Tokyo foreign exchange market, the exchange rate between the won and the yen is calculated as 900 won per 100 yen. Currently, South Korea announces daily exchange rates calculated in this manner for 20 different currencies, including the Japanese yen and the Chinese yuan.

Then, why do exchange rates fluctuate frequently?

Prices are determined in the market. If the market is active, there’s a tendency for a product to converge to a single price according to the law of one price. In reality, there can be violations of this law, but in such cases, savvy individuals will attempt to trade for arbitrage.

For example, let’s say a CD costs 10,000 won in the eastern village of a country where 100 people live, but the same CD is sold for 7,000 won in the western village. People can easily make a profit of 3,000 won by buying the CD in the western village and selling it in the eastern village, assuming negligible transportation and other transaction costs. If this trading continues, the prices in both villages will eventually balance out, meaning they will reach the same price.

This kind of trading is known as arbitrage, a transaction that profits from the price difference of the same product being sold at different prices in two or more markets. Hence, arbitrage eventually eliminates all market price differences.

Consider arbitrage when there are multiple markets. For instance, in New York, if the exchange rate between the euro and the dollar is 2:1, and between the yen and the dollar is 5:1, then logically 2 euros should exchange for 5 yen. However, if 2 euros are exchanged for 4 yen in the Tokyo market, anyone can make a huge risk-free profit due to the higher valuation of yen in Tokyo. Therefore, someone could exchange 1 million dollars for 5 million yen in New York, then exchange these for 2.5 million euros in Tokyo, and finally exchange these back to 1.25 million dollars in New York, making a profit of 250,000 dollars without much effort. This trading would continue until the price difference disappears.

This arbitrage-determined equilibrium point can be considered as the fair exchange rate.

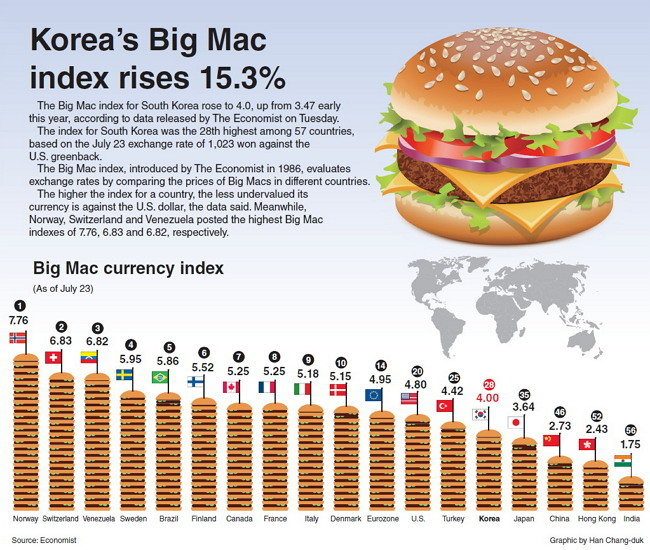

Economists call the theory that exchange rates are determined by arbitrage the Purchasing Power Parity (PPP). Therefore, the exchange rate is meant to equalize purchasing power. For example, if a McDonald’s hamburger costs 5,000 won in our country and 5 dollars in the USA, the exchange rate should be 1 dollar to 1,000 won.

The market uses the Big Mac index to compare the purchasing power of different countries. Developed by The Economist and first published in 1986, the index showed that a Big Mac cost 3.54 dollars in the USA in early 2009, and when converted to dollars, a Big Mac sold in Korea cost 2.42 dollars. As of early 2024, the Big Mac index is 5.69 in the USA and 4.11 in Korea. Over roughly ten years, prices in both countries have risen by nearly 70%, but the price difference between the two countries has not significantly changed, indicating that McDonald’s hamburgers are still cheaper in Korea. This can be interpreted in two ways: either our country’s prices are lower, allowing for the purchase of more hamburgers with the same amount of dollars, or our currency is undervalued. According to PPP, it’s the latter.

However, exchange rates are not solely determined by PPP. Price distortions such as trade barriers and tariffs exist everywhere, and transportation costs are not negligible. Additionally, there can be differences in market efficiency and price rigidity between countries. For example, if import car prices changed with every fluctuation in exchange rates, it would erode customer trust. Ultimately, importers must use pricing policies suitable for their market’s conditions, so few economists believe exchange rates are solely determined by purchasing power.

Despite its limitations, PPP helps envision the big picture or long-term trends of exchange rates. If exchange rates form a major trend based on purchasing power, then the expected exchange rates from interest arbitrage would create a relatively minor trend.