Money is an essential means for economic growth. It reduces transaction costs in the market and enhances trust. For transactions to proceed smoothly, sufficient money must circulate in the market. Money backed by gold may be more trustworthy, but money backed by the taxation of citizens also performs its function relatively well. The problem is that the value of this currency can sometimes become unstable. An unstable currency means a loss of trust, and as trust diminishes, transaction costs increase. Naturally, transactions in the market decrease, ultimately having a negative impact on the economy of a society.

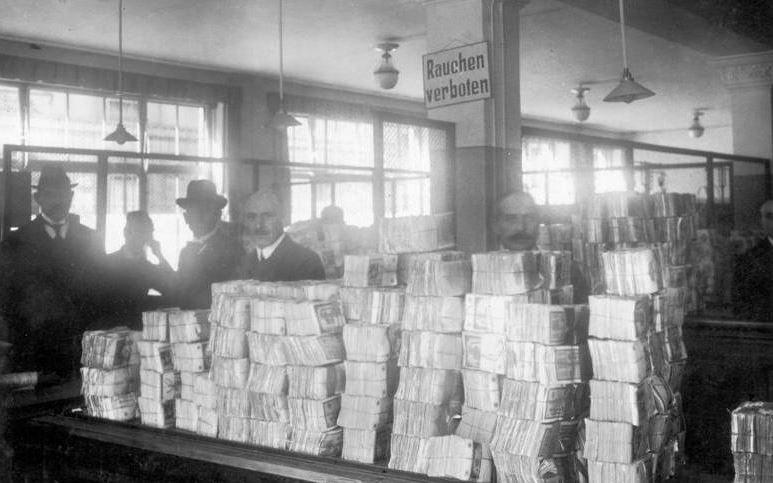

After World War I, the world witnessed a level of currency instability that had never been experienced before. The stage was set in Germany, Hungary, Poland, and Russia. Specifically, in 1923, Germany experienced an astronomical price increase of 3,250,000% in just one month.

Germany had already entered a phase of hyperinflation in the summer of 1922. This was because the Weimar Republic government began issuing new government bonds at bargain prices to pay for war reparations. As debt increases, so does the amount of money. On January 11, 1923, French and Belgian troops occupied the Ruhr industrial area, the heart of German industry, as retaliation against the German government’s declaration to postpone reparation payments. This triggered a panic. People exchanged marks for foreign currency or tangible goods as soon as they got them. When the situation reached this point, the mark was practically worthless. Since the country was essentially without currency, the economy eventually collapsed. On November 15, 1923, Germany halted its currency printing machines and carried out a currency reform, converting 1 trillion marks into 1 new mark. And the German central bank issued a new mark pegged to the price of gold in the United States.

After the 1950s, this type of inflation did not disappear. Argentina and Brazil also experienced record inflation from 1989 to 1990. The root cause of inflation is an excessive increase in the money supply. Such an increase occurs as government fiscal spending expands. Remember, debt is money.

The instability of money’s value can be so powerful that it can change the regime of a country. Therefore, Keynes said, “The best way to undermine the foundation of society is to induce inflation.” When prices skyrocketed in areas controlled by Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist Party, the Chinese Communist Party easily took control of these regions. The successive overthrows of governments in Brazil, Chile, and Argentina by the military were also due to severe inflation.

When confidence in currency collapses, purchases of tangible assets increase, and preference for foreign currencies emerges. Ultimately, citizens suffer economic hardship due to high prices. Milton Friedman warned in his book “Money Mischief (1994)” that inflation is a deadly disease that, if not cured in time, can collapse society as a whole.

Currency is thus an essential existence for economic growth but can also cause problems by collapsing market trust. Although economic crises caused by increases in the prices of oil and grain, like real prices, have not completely disappeared, most of today’s economic crises arise from financial instability.

The market economy operates on a price system. Instability in currency shakes prices, and if the price system does not work well, the market contracts. For the market to grow, not only free competition but also trust and stability in the value of money are essential.

The government’s efforts to maintain stability in the currency while helping the economy are called monetary policy. Alongside fiscal policy and tax policy, monetary policy is one of the important macroeconomic policy tools. The difference is that while the government directly carries out fiscal and tax policies, monetary policy is typically handled by the central bank, which is not classified as a government organization by law. As history has shown, entrusting an independent institution with this task benefits the entire nation by keeping it free from political interests.

Monetary Theory: Two Clashing Theories of Money

European Spain and Portugal thought that gold and silver exploited from America and Africa helped these two countries become wealthy. Here, gold is literally money. It is not money made by a country’s government but a key currency used worldwide. But can a country’s economy be helped by an increase in money that is not related to gold, as it is today?

Many economists, after reviewing history, testify that an increase in money can stimulate the economy. Of course, different conclusions may arise depending on how data is used and interpreted, as macroeconomic theory does. Nonetheless, it seems reasonable to think that an increase in currency can help activate the economy, provided that there is an appropriate supply of money in line with the growth of the real economy. But what is considered appropriate?

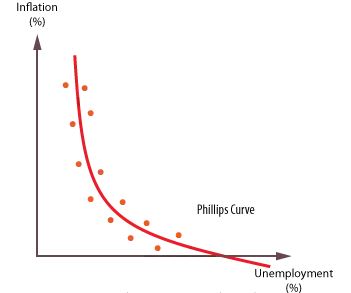

There is a simple economic theory that increasing money improves the economy, known as the Phillips curve. It simply states that ‘the inflation rate and the unemployment rate are inversely proportional.’ If this is true, then the government can regulate the economy by controlling prices during periods of excessive boom or recession.

For example, let’s say the town of Yeolbang experiences an economic downturn, leading to a significant increase in unemployment. And then, imagine the government somehow manages to increase the money supply. Because of this increase, more money would circulate, eventually leading to inflation. Inflation refers to a rise in the price level, and since the price level is inversely related to the unemployment rate, unemployment would decrease.

However, it’s not that simple. If mishandled, it could lead to stagflation, a situation where, contrary to what the Phillips curve suggests, both inflation and unemployment rise simultaneously. Many economists today believe that the Phillips curve may hold in the short term but not necessarily in the long term, indicating that the exact answer is still unknown.

There’s agreement, though, that without an increase in money alongside growth, the economy could stagnate. A lack of money leads to deflation, or falling prices. The Gold Standard era showed that scarcity of gold could lead to deflation. For instance, the discovery of gold in California in 1848 led to the Gold Rush, attracting people worldwide by 1849, known as the Forty-Niners. However, gold was not infinite, and by 1952, as the Gold Rush tapered off, the U.S. experienced deflation. Conversely, the discovery of new gold mines in Yukon, Canada, in 1897 stimulated the Canadian economy. This shows a clear correlation between money and the economy. Today’s money is undoubtedly more unstable than gold.

So, what is the relationship between today’s money and the real economy? Let’s understand it as economists do in the financial economy, using a single equation.

MV = PY

This can be expanded to the quantity of money (M) times its velocity (V) equals the price level (P) times the output (Y). This equation, presented by Irving Fisher, a monetarist economist from Yale University in the 1920s, asserts that the quantity of money and its velocity always match the volume of real transactions. Since this is an identity equation, it is always true by definition. However, this equation has sparked intense debate between Keynesians and monetarists.

Money supply refers to the amount of money circulating. The velocity of money is how often that money is used over a certain period. For example, in a town of 100 people called Yeolbang, if there’s a total of 10 billion won, all in 1-won notes, and each note is used 5 times a year, the velocity of money in Yeolbang is 5. Thus, the total transaction amount in Yeolbang for a year is 50 billion won (10 billion X 5).

These transactions mean someone made sales, representing the total value of services and goods produced in a year. Hence, the town’s total production is 50 billion won. This money will be distributed to those who participated in production as income, meaning the total income is also 50 billion won. Since total production is the quantity of services or goods produced multiplied by their prices, it can be expressed as the quantity of money (M) times its velocity (V) equals the price level (P) times the output (Y).

We’ve discussed how increasing M, the money supply, can stimulate the economy. Since Fisher’s equation must always hold, an increase in the money supply must affect other variables in the equation. Introducing new money into Yeolbang, monetarists argue that rational individuals will not change their behavior significantly, leading only to an increase in prices. According to monetarists, with the velocity of money and output fixed, only the price level will rise to match the increase in money supply.

On the other hand, some economists believe that an increase in money supply will make people feel wealthier and increase spending. This consumption increases the velocity of money, and producers, seeing increased demand, produce more. Economists with this view are called Keynesians.

Many economists agree that increasing money and its velocity can, in the short term, increase production. This was evidenced by the massive monetary supply provided by countries in response to the 2008 financial crisis.

However, economists don’t universally agree on this approach. Keynesians argue for regulating the velocity of money through government action, while monetarists emphasize controlling the money supply.

How can Keynesians propose controlling the velocity of money without increasing the money supply? The government could issue bonds to draw money from wealthy individuals, using this money for large public works and distributing jobs, creating new income and boosting consumption without printing new money. The overall money supply remains unchanged. Wealthy individuals earn interest on the bonds, so they don’t lose out. People in the town who earn new income will spend it, and those who sell goods to them will also earn income, increasing transactions and, consequently, the velocity of money.

According to Keynesians, it is possible to regulate the economy without increasing the money supply. On the other hand, monetarists argue that if the government issues national debt in such a Keynesian manner, taking money from the wealthy, the money supply in the market will decrease. Consequently, the lack of money needed by others will drive up interest rates, leading to a decrease in the money supply. An increase in interest rates means borrowing becomes more difficult, and as debt decreases, money disappears. Higher interest rates will lead people to use less of others’ money, thereby reducing the money supply as much as debt decreases. Considering that debt is money, it can be seen that even if the velocity of money increases, it cannot offset the decrease in the money supply, rendering the overall effect meaningless. Therefore, monetarists advise directly increasing the money supply.

Another difference between monetarists and Keynesians lies in the velocity of money. Keynes argued that the velocity of money changes. Moreover, he believed that supplying money during a recession has little effect due to the liquidity trap. However, monetarist Milton Friedman argued that the velocity of money and the speed of consumption do not change significantly. In simple terms, the velocity of money is related to people’s spending habits, and thus, the velocity of money in a society remains relatively constant.

In fact, the velocity of money can only be known after the fact. It can be speculated that the velocity of money increases during a boom and decreases during a recession, and that liquidity might decrease if the risk of default increases. However, the velocity of money is influenced by new societal changes such as consumer spending patterns, credit cards, online payments, and mobile payments, making it difficult to predict its speed. This presents a challenge in economic policy. While future projections can be made based on past data, it is difficult to be certain due to the many components that influence each other and change.